On the seventh day, I rested.

There was no more real work for me to do. The thallium was beyond my control. It would do what it would do. I’d kicked all the rocks. The avalanche would come on its own, or not.

The alarm buzzed me awake at seven. I would have slept longer, but I had to go to ten o’clock mass. After all, the commandment reads, “Thou shalt keep holy the day of the Lord.” I was up early. You know how I hated Valerie’s couch. She was punishing me because I had punished myself at the party. It wasn’t my fault. Skip made a very good martini.

I had skipped the meal at the fundraiser. Not because I was afraid the serving staff would scramble up the plates and deliver the dosed items to random members of the crowd. My dose had been accurately delivered way before the meal. It was a toxic smart bomb. I didn’t eat because I just hate banquet food. Besides, I wanted to get drunk, and food doesn’t mix with that ambition. I needed the booze because I hate banquet speeches even more than the food. I vaguely remember watching the dignitaries eat. I raised my glass to the ship of fools.

I hadn’t used any thallium on the head table. That had never been the real plan, only a wet dream of vengence that gave me the illusion of control when I most needed it, face-to-face with Shuldik. I needed to be cool when I spoke to him. Knowing I had the power of that poison in my pocket gave me the edge I needed to pull off the bluff. I had considered doing it. I stood by the plates with the other three thallium packets and thought about ad-libbing. But that hadn’t been my choice. Besides, I had decided to become a murderer, not a mass murderer. I didn’t want this honest little shot of justice diluted. Justice was coming for Shuldik et al, not the rich in general. I’m no Bolshevik.

Truth is, though, I’ve always got a new scheme flapping around, trying to find a perch in this sociopathic head of mine. So, even if I’ve got one plan in motion, I always consider alternatives. When I was running this alternate plot through my head on Friday, I had gone over all the factors of the homicidal fantasy. If I was going to poison someone, I would need to isolate the dose. It would have to be placed in something only my target would consume. I would have to be there to make sure he consumed it completely. I do like to be in control. Everything I had envisioned had come together so far. When Father Corleone told me about his transfer and how the Monsignor would announce it at Mass on Sunday, I knew how his end could be arranged. It all seemed so perfect. Like I said once, all I needed was a weapon. I always had a surplus of plans.

During the Mass, the priest who is celebrating uses a large host for the consecration. He breaks it as Jesus broke the bread at that other Last Supper. Then the celebrant, all by his lonesome, places that large broken host in his mouth. “Take you this, and eat.” To deliver a large dose of thallium, all I needed was access to the host they would use; the host the altar boy would set up the day of the mass. Torey was an altar boy. That part wasn’t my doing, but I could exploit it so easily. The plan satisfied my need for a showy and symbolic piece of divine retribution. So many choices.

Father Kenneth Corleone had, in his last act as Pastor of Infant of Prague, tried to disuade Kim from letting the boy serve the Monsignor’s Mass, but her opinion of Kenny had been trashed by Shuldik. She would barely speak to him. That Sunday morning, I picked up the phone and called her, hoping against hope, that I could change her mind.

“Don’t let Torey do it, Kim.”

“You don’t know him, Marty. You’ve never been his father. You’ve never been involved.”

“You didn’t want me involved.”

“You never argued with that decision.” Kim was telling the truth about that.

I couldn’t say anything to defend my callous and selfish behaviors. I could only manage a weak, “I should have.”

“Torey loves being an altar boy.”

“Kim, don’t you understand what he’s been through? He’s been raped…”

“Don’t say that. It’s all in the past. He’s doing much better today. Besides, he loves serving Mass.”

“But it’s with him, with the Monsignor.”

“For once in your life, be practical, Marty. Think of someone besides yourself. He’ll be the next Bishop, Marty. He’s a very important man. He can get Torey into the Prep School.”

“Let me talk to Torey.”

“He won’t listen to you. He doesn’t trust you.”

“How do you know?”

“He told me, Marty. He cried himself to sleep. He kept saying that you didn’t understand. That you didn’t know what had really happened. He just wants to forget about all of this. We have to move on, Marty. Admit it. You don’t know what happened.”

“Kim, listen…”

She hung up. She was so blind. She had convinced herself that Mikey had been the molester. Thanks to Liz Nice, so had most of the city. Kim would never even ask Torey. I knew her. “That’s all in the past now,” she’d say. Even if she did ask, Torey was not about to tell his mom anything. He was just like me. He was in secrets mode. God, forgive me. Torey was going to serve the Mass.

Kim was wrong. Torey was wrong. I did know the truth. In fact, after Kim hung up, I wrote it all down. A simple little note. It was my last chance to save my son. There was only the slimmest of chances it would work, but I had to try. I folded the paper in half and put it in my pocket right next to another little something I’d prepared for dear Leo Shuldik. Then I went into fantasy mode. That’s where I would stay until it was all over. I didn’t feel any guilt at all. It was just a question of how cold I could be. Could I ask Torey to do it? A simple thing to ask a son to do – be my accomplice. I had decided I could kill. We could kill. Of course the way to do it, really do it, had been irrevocably set in motion. There were other visions at work.

Thursday, after I’d finally found Torey, after I saw the ring, Best Buy, and knowing Redlands was sure to show up at Val’s, the plan had crystallized like thallium nitrate. My nerves burnt with the thought of it. I was about to commit the greatest sin a man could commit. I cut myself off from God. It was the only way I could do this. I knew then, it was the only way. I knew exactly what I was doing. I hoped no one else — especially Vandy — caught on. If you feel like I’m hiding, or lying to you, I’m sorry. I’m just trying to tell you what I was thinking at the time. I had my mask on.

Valerie and Sally were up and dressed in plenty of time as I paced back and forth in the kitchen. Val wanted to come to the church to keep an eye on me. She knew me too well. Sally had to come along to keep an eye on Val. Sally knew me too well. Vandy had frisked me six times before we got on our way. Vandy knew me way too well. Vandy was too good, too suspicious, to mess around with. He had a talent for seeing criminal intent when it flickered in my eyes. Those were Vandy’s strengths, and I played off them.

The last time Vandy patted me down was just as we were getting in the car. This time he found something in the cigarette pocket of my sportcoat.

“What’s this?” He held up two little plastic packets full of fine white crystal.

“Ah, oh that’s just sweetener for my coffee, Vandy.” My eyes couldn’t have flickered more.

“Bullshit.” Vandy shook his head. “You were going to poison the son-of-a-bitch, weren’t you? Dose him with…” He sniffed at the packets. “What is this stuff?”

“Ah, just sweetener, Vandy. But don’t sniff it. And please, go wash your hands.”

He literally ran inside the apartment. Not easy for a man his size with such overstressed knees. When he emerged, his nose still had some soap suds on it. “You asshole.”

“Sorry, Vandy. But I had to try.”

He thought about that for a second, sighed, and pushed me into the car. “You’re lucky I was waiting for some kind of move like this, Tools. I saved your ass. I understand what you feel. But you’ve got to let the police do the work. You can’t be a vigilante. I can’t let you do your own remake of ‘Monte Cristo,’ or any cheap Clint Eastwood imitation.”

“Yeah, Vandy. You’re right.” He was right.

“What did he try now?” asked Sally from the driver’s seat.

“Nothing,” Vandy said. “Just get us to the church on time, huh?” He gave me one of his protective looks. Vandy could relax now. He’d foiled my plot. I liked Vandy when he was relaxed. It’s a fact that when you want to sneak something by a guy like Vandy, a sharp guy, make sure he finds something you’re trying to sneak by him. Make sense?

As Val got in the car, I grabbed her hand and gave it a squeeze. “Val, I know you’re coming along to support me in this, my hour of need. Just don’t embarrass me. It’s a Catholic Church and…”

“And what?” Val asked.

“You look very Jewish.”

“Shut up.”

The drive out to the church was a blur to me. As we arrived, I saw Kim and Torey. I hopped out and went to Torey. I hugged him. He held his body back. Hugs were uncomfortable for him. I didn’t press. I spoke to him and him alone.

“Are you all right? Can you do this?”

He avoided eye contact. “Yeah, I’ve served Mass before.” He was flat, passive.

“He won’t hurt you.”

“You gonna’ protect me, Dad?” Torey had a blade for a tongue.

I grabbed him by the shoulders, maybe a little rougher than I should have. “Yes, Torey I will protect you.”

His eyes teared up – just slightly. “I’m scared, Tools.”

“I’m scared, too, Torey. Trust me. Trust me just one time today.”

“You’ll protect me?” The sarcasm was almost gone.

“I will. And I need you to promise me something.”

“What?”

“Take my hand when I ask you to.”

Torey hesitated. “That’s all?”

“That’s it. Just hold my hand when the time comes.”

“You’ll be there when I need you?”

“I promise, Torey. I’ll be there.”

“You better not be lying, Tools.” He wouldn’t call me Dad, and it had to be all right with me. It was.

“Can you make sure the Monsignor gets this?” I held up a little folded piece of paper. “Put it on the consecration host.”

“I don’t know…”

“I’ll take you out for some fun.”

“O.K..” Still no expression in his voice. “Maybe. I’ll do it.”

“Are you sure?” I slipped the folded paper into his sport coat pocket. “You can do that?” Torey nodded. He wasn’t making eye contact. He was lying. I only had one chance left to convince him. “This is for you.” I handed him a little note. “Read it.”

He held it in his hand, and as he took in the words, his hand started to shake. At first he looked shocked, and I thought he might cry. Then he smiled a little. He looked up at me.“You do know what happened?”

“I know, Torey. I know what happened. It wasn’t your fault.”

“You know what happened.” He looked relieved. Like he was a real kid again – a real kid with a dad who would protect him. With the last secret gone, he trusted me a little – all because I did know. “O.K.” He looked at the folded paper meant to go on the host. “I’ll do it.” This time he meant it. “And then you’re taking me to Gizmo’s Arcade next week?” I’m ashamed, but, yes, I had added another little bribe, a father son trip to electronic game heaven. I’m always hesitant to trust the truth. It doesn’t always work.

“Sure, Torey, sure. We’ll go to the arcade.” Torey gave me a curious look. I’m still not sure what it was, pity or pride. I just couldn’t tell. I watched as my son headed in the sacristy door. He looked back at me. He was still holding my note in his hand. He almost looked like he loved me. What would he feel when he walked out of that door after…? I rejoined the rest of the Fearsome Foursome, and we went in the church.

I had cased it the night before, as you no doubt recall – on the way to the party when we stopped to say goodbye to Father Corleone and his mom. I had to see it. The entire script had to play out. I needed access to the consecration hosts. So that all of it could flicker in my eyes. Every scene had to be acted out in full. I had to be able to imagine it happening there. I told you at the beginning of this whole thing, I have a good imagination.

The sanctuary seemed smaller that morning when it was full of people. We sat about halfway up. I never sat in front. Today, I especially didn’t want to be too close to God. Besides, he makes me nervous when he’s indoors. I heard that in a movie once. I thought of it again as we sat down in the pew. This would be my first Mass since God let the Cubs lose the ‘84 playoffs. It would be my last. I swore. Unless the Northside boys made it to a World Series game seven. Yeah, I was thinking about baseball. I didn’t want any giveaway to show on my face.

I sat next to Val. Sally sat to her right, protectively. Vandy was on the aisle. He was going to make sure I didn’t make any rash moves towards the Monsignor, but he was pretty sure he’d nipped my plot right in the baggie. I kept my eyes to the front. I didn’t look at anyone. I didn’t want to know who was there.

The place was filling quickly. There was a low buzz in the sanctuary. The word had gotten around that Father Corleone had been transferred. Rumors were everywhere. The Monsignor was here. Something big was going to happen. The congregation was split between sadness and “it’s about time.” The organist began to play. It was the Mozart Mass. I love Mozart, and the Mass was his masterpiece. Was it to be my masterpiece, too? For good or ill, I was the composer of this piece.

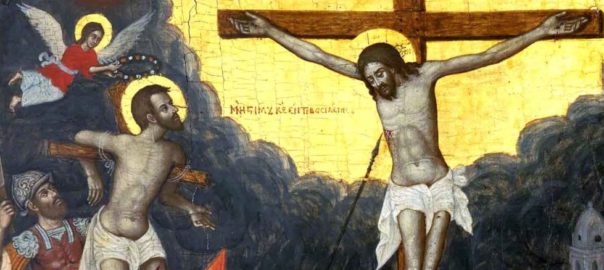

Torey led as the two altar boys entered from stage left. Behind them stepped the Very Reverend Monsignor Leo Shuldik, clad in a deep red chasuble, the cross in back, ornamented by stones and two gold-threaded, embroidered, sacrificial lambs holding crooks topped with the legend INRI, Jesus Nazarenus Rex Judaeorum; in English, Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews. By tradition, it had been painted on a board and nailed to the cross above Jesus’ head to mock him. I almost nudged Valerie to comment on it, but I didn’t. I wasn’t feeling like a smart ass now that the pageant had started.

Shuldik wore red because it was the Feast of the Four Crowned Martyrs. They were four Roman stone carvers who had refused the Emperor Diocletian’s order to carve a statue of a Roman deity. Had he asked them to carve a bust of Thalia? I don’t know. Red was for martyrs. I regretted that, but it was beyond my control. I had set this in motion, but it was all beyond my control now. The pew seemed hard and uncomfortable. I remembered some chairs in an auditorium where Doug Hunter and I had watched “Hatari.”

The music was beautiful. The ritual was well underway. The Introit, “I will come unto the altar of my youth.” The Kyrie, where the classic Greek words praise the Christ. The reading was from Paul. I don’t like Paul. He was an organization man. He had the heart of a consultant. He had warped the gentle message of the Nazarene. Sorry, that’s how I feel, and I’m trying, I have been trying, not to hold back anything. I want to tell you everything. You will be the final judge here.

The Gospel was read by a deacon with a long gray face. It was from Luke. I don’t want to bore you, but listen, it is important that you understand. It is the story of a dishonest servant and ends with an instruction from Jesus’ own mouth.

He says, “…Whoever is faithful in very little, is faithful also in much. And whoever is dishonest in very little, is dishonest also in much…No slave can serve two masters…You cannot serve God and serve wealth.”

If the Monsignor did not understand, I did. If the good priest did not feel shame, I did. The message was for us both. But I could change nothing now, nor could he. The stone was rolling downhill. It was all gravity now. The man had stepped off the cliff.

The robed apparition, which is how he seemed to me at that point, mounted to the pulpit and began his sermon. He spoke of the unfortunate falling away of Father Corleone and asked the parishioners to remember the misguided in their prayers. And then he quoted from Ezekiel.

“Says the Lord God. I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from their ways and live. Turn back from your wicked ways… and say to your people, The righteousness of the righteous shall not save them when they transgress…in the iniquity that they have committed they shall die…” He spoke on. I was grieving and heard little else. I hoped I would be forgiven. But I could not ask for forgiveness on that Sunday. When he finished, half the congregation stood to applaud. I did not join them. I kept my eyes fixed on Shuldik.

At the Offertory, the host and the wine are carried to the front by two members of the congregation. This Sunday two little boys, about ten, in navy blue sweaters, solemnly marched down the center aisle carrying the bread and wine of this communal meal. The celebrant stood, flanked by the servers, and accepted the gifts.

Torey seemed impassive. Shuldik had probably been pleased to see him when he had entered the sacristy before Mass. He had probably taken it, after his initial nervousness, as a confirmation of the deal he was about to make. I had no choice but to hope he would. There was money on the table, and Shuldik knew how to deal with money. He saw my demand for the three million dollars as a sign of weakness. The Monsignor saw me as a victim of greed. He was used to exploiting such weaknesses. Now there was no hesitation, no lack of certain confidence in the man. He was robed in red and gold. No wind could blow him away.

At the altar, the ritual meal reached its center. Shuldik was about to perform the transubstantiation. He would bring Christ himself back to earth in the bread and wine. I couldn’t be sure from where I sat that the Monsignor had noticed what was on the host. But there was a short pause, and it looked almost like he flicked at something with his right hand. Through the wireless microphone he was wearing, the entire church could hear a shakey deep breath.

He recovered quickly and spoke the words, “On the night he was betrayed, he took the bread into his hands and said… This is my body…” He raised the large host in his two hands above his head. The Monsignor offered the gift to God himself… Torey rang the sweet bells. “This is my blood…” He raised the chalice and Torey called us all to witness with his bells. It was all so right and wrong at the same time. I knew I would go to hell for what I had done.

The ceremony moved on inexorably.

“Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us…”

Shuldik invited the congregation to exchange the Peace of Christ. He clasped the hands of the Deacon. He took Torey’s hand…. I shuddered.

The people in the pews, turning this way and that way, exchanged the greeting. It was formal and without real human feeling. I took Val’s hand and our eyes met. “The Peace of Christ.”

Shuldik was chanting the Agnus Dei. “Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world… Lord, I am not worthy…”

Facing us, Monsignor Leo Shuldik placed the consecration host in his mouth. He paused reverentially as it dissolved on his tongue. He swallowed and closed his eyes, meditating on this, the holiest of moments. God’s son slipped down his gullet. The divine judgment was now within him.

Carl Vandy looked at me. He realized then what I had intended to do with the packets of thallium. He shook his head and wiped his fingers on his pant legs unconciously. Then he looked at Shuldik. Was the man’s face flushed? No. Vandy looked back at me. I nodded at him. “No, Vandy,” I mouthed.

Vandy’s face was puzzled. He was trying to figure out why I had taken my defeat so well. He was trying to figure out what he had missed.

Shuldik drank of the Saviour’s blood, and he invited all to join him. His face was the face of death to me. Was I the only one to see it? Vandy looked over at me. Did he suspect? Probably he felt some disturbance in the Force, but no, he had no idea what was to happen. Valerie did not know. Sally did not know. Torey did not know. As for me, I was so afraid that I did.

As the music opened the church to heaven itself, ushers began directing people into the aisle. One row at a time, they filed to the communion railing. Shuldik met them there holding the ciborium, a gold cup full of small, consecrated hosts. Torey stood beside him holding the gold dish, the patin. He would follow under the priest’s hand as he extended the small breads. The worshipers would either accept them in their hands, or, more traditionally, on their outstretched tongues. Torey would remember their tongues as I had.

One row at a time, the ushers gravely admitted the people to the central aisle. With downcast eyes and folded hands, they slowly but steadily approached, received, and returned to their pews by the side aisles. The music was beautiful as the organ traced Mozart’s mathematically constructed praise in the air of the church.

It was our pew’s turn. I motioned for the others to remain seated. They could not join in this meal. The Catholic Church does not invite outsiders to partake of this feast. Vandy wanted to follow me. He might have seen something on my face that worried him. He was too late. I slipped sideways down the row past their feet and stepped onto the path that led to my son and his monster. Vandy did a quick frisk on me as I brushed past him. There was nothing to find. My eyes were on the red carpet that led us forward. I took small steps. Where was God’s judgment? My hands were folded together at my waist. I moved closer to the railing. I could hear Shuldik.

“Body of Christ.”

The communicant replied, “Amen.”

“Body of Christ.”

“Amen.”

I moved closer. And then I could smell another presence. It was the smell of tea made with oak leaves. I could feel his breath behind me, as he moved the air, behind me. We started to synchronize. You may think I am crazy, but we did, and I felt it. Our pulses were one.

I stepped up to the Chancellor. He recognized me. His pupils dilated. I noticed. I was deep in his eyes. I could feel Torey to his right. I didn’t want to look at my son at that moment.

“Body of Christ.”

My hands were cupped in front of me, my tongue extended itself. What bargain would the Monsignor make? What difference would it make? The lots had been cast at the foot of the cross. The robe would not be divided. I would kill. I’d promised. I held my hand a little forward and bent my head. Shuldik picked out a host with his thumb and forefinger. The Monsignor’s ruby ring sparked blood red. He reached out and was about to place it on my tongue. As he let go of it I pulled back.

Shuldik was startled.

The host dropped as if in slow motion. It tumbled down and landed in the middle of the golden paten. Torey had made the catch. The Monsignor was suddenly confused. He remembered what I had said the night before.

“If the host is not on my tongue, you will die.”

The Monsignor could feel there was something very wrong. He felt it in every nerve. His face showed all of his fear.

I looked down at Torey and smiled. He smiled back. The moment had come. I held out my hand. Torey dropped the golden paten, and it clattered on the marble. The body of Christ was on the floor. And then he took my hand.

“Let’s go, son.”

“Yes, Dad.” We walked away across the front aisle towards the side door of the church. “Don’t look back, son.” He didn’t. Maybe he knew the tale of Lot’s wife. Heavenly fire was about to rain down on the corrupt. I didn’t see what happened next. I didn’t have to. It wasn’t meant for my eyes. It wasn’t meant for Torey’s.

Monsignor Shuldik continued communion in a daze. I have to think that he felt the mistake in the air along with the murmur from the congregation. But it was no mistake. It was no accident. Did he feel what I wanted him to feel — very warm, suddenly, almost hot? As a priest he should have stopped and picked up the dropped host, but he must have been stunned –stunned by what he saw on the host before the consecration, stunned by my sudden refusal of the bribe, stunned like a pig in an abatoir. Val told me later that he acted like an automoton. He held up another host. Someone stepped forward. Someone I had sent.

“Body of Christ.”

Did he feel like he was falling? Beyond the host he held in his fingers were the eyes of Officer James Redlands.

I found out later that Shuldik didn’t know him all that well. He had seen him at some of the Catholic Life meetings. He knew that the policeman was Kensington’s creature. He had always been careful to keep a safe distance between himself and the young zealot. Now that safe distance was gone. And looking into Redlands’ eyes he surely recognized something else. I think all of us do when a man like Redlands looks into our eyes.

Torey and I were almost at the side door. I heard the voice behind me, echoing through the nave — that voice from the Albino Farm.

“It is finished,” said James Redlands.

I wonder if he raised the gun slowly, or if he snapped it up like he was on a parade ground – no matter. The muzzle was two inches from Shuldik’s forehead. The blast echoed, and the Mozart coming from the pipe organ turned from mathematic’s pure form into chaos and then sudden silence, a half measure past the concussion.

People screamed.

I had heard it behind me as Torey and I continued parallel to the railing and out the side door. Vandy had been watching me intently. Only at the last second had the detective’s eyes found Redlands and understood the implications. I heard Vandy start his rush up the aisle – too late. I could hear the confusion and panic inside. I heard Vandy’s shot as he put a bullet into the heart of James Redlands. Mad dogs must be shot down. I think even James Redlands knew that.

I didn’t see it happen with my eyes. Torey did not look back. He did not turn into a pillar of salt.

The sounds were horrifying enough. Maybe I was even glad that Torey was there to hear the noise that hell’s gates can make when they open wide. If it seems a cruel gift to you, then you do not know what boys like Torey, and me, and Douglas Hunter know.

We stepped out the door. The boy was still holding my hand.

“You all right, Torey.”

“Yeah.” A short answer. Torey was thinking it all over.

“Is Mr. Kensington really dead?” There was actually a taste of little boy in his voice, as if he was asking, “Is the moon really that far away?”

“He’s dead, Torey. They can’t hurt you anymore.”

We kept walking towards the car. There was screaming and crying inside Infant of Prague. People were starting to rush outside. A woman fainted just outside the front door. Scores of frightened voices mixed into an indistinct, “Bread and butter bread and butter bread and butter…”

“You made him kill the Monsignor didn’t you?” Torey was looking up at me. There might have been love in his eyes, or it could even have been fear. The two are very much alike sometimes.

“Yes I did.”

“Was it like that story you told me about that time when you were in prison?” Torey knew about the biker I’d turned loose on the gang banger to protect my cellmate.

“I shouldn’t have told you about that. Your mom got mad.”

“You told me lots of stuff. Like how you stole things. How you did stuff.”

“I was trying to impress you.” We reached the Sally’s car. Torey hopped up on the hood. Some members of the congregation were rushing through the parking lot, jumping into their cars. Whenever there’s a public murder, everyone acts guilty. I could hear some sirens in the distance.

Torey was stroking the pre-adolescent down on his chin, just like it was a beard – thinking hard. “You showed the cop that videotape?”

I was fidgeting. I didn’t know if I should answer him. He was just a kid. This was serious, amoral, twisted shit. Then I closed my eyes and saw the image of naked Torey and the man’s hand. That’s the last time I’ve intentionally let that memory loose. Lord knows, those searing pictures pop up in my head often enough without me wanting them to. You won’t find a single parenting book that recommends what I decided. But to me, it seemed proper. Torey had a right to all the answers.

“Yeah, I gave him the tape. That night I found you.”

“But it was a purple ring. Why would he kill… kill… Why?” Torey looked off towards the church. The first of the police cars was screeching to a stop at the foot of the steps that led to the vestibule. “You knew it was purple. You saw it on the Best Buy screens. So…” Torey looked at me hard, like a tough old con with a tatoo. Survivors can age in a heartbeat.

“The day after you went back to your mom’s, I went a few places.” I could still smell the plastic closeness of the haz-mat suit I’d worn at the lead plant, the ginger in Kensington’s bathroom, the mold in the air at Redlands’ house. I went so many places. “You showed me what to do, Torey.”

“I did?”

“Yeah. Simple for a smart kid like you. Something I might have missed.”

His face lit up. “I adjusted the color on Valerie’s television.” He was almost a kid again — that curious transformation again. Torey’s face looked like he was solving a jigsaw puzzle on a rainy afternoon. “You went to the cop’s house.”

“Yeah.” I admitted it to Torey. The kid had no idea how lucky I’d been. If Redlands had owned a nice, modern set, I’d never been able to skew the color settings. But, of course, Redlands was not a man of the material world. He wasn’t into all the latest gadgets. Besides, on a cop’s salary, he wasn’t likey to have one of those computer chip-controlled plasma screens. Luck. I brought along the dubbed tape I’d made at Best Buy, just to make sure my adjustments were right. I’d risked Father Corleone’s life, sending him out with Redlands and the tape.

“You made him think what you thought at first — what Pies’ mom thought…”

At least five more cop cars had pulled into the lot, and two ambulances. Parishoners cars were screeching out the other exit. A crowd was milling on the sidewalk. I could see Vandy talking to a few officers. He looked upset. He didn’t like killing people.

“Yeah.” There wasn’t much else I could say.

I learned it in prison and on the street. Manipulation is the best protection. When my cellmate was threatened, I found a hypersensitive biker to wipe out the Frito Bandito boy. I had used it on Mikey in jail with the tattooed Sponge Bob fan. I manipulated everyone. Even my own kid, in the end.

The most dangerous weapon, especially for a smart guy, is always somebody else. Redlands was the most dangerous weapon I had ever tried to pick up. Until I felt him behind me in line for communion, I didn’t know if it would work.

What I did know was that Redlands was a human time bomb. The question was, when would he go off? With his religious psychosis going, I wanted him to see the tape himself. That’s why I hoped he wouldn’t miss hearing about Torey’s re-emergence at Valerie’s house. I know, I told Father Corleone to keep him from finding out. But I always knew the young priest wouldn’t be able to succeed in that seemingly simple task.

I wanted Redlands to take the tape. I wanted him to watch the tape. I needed Father Corleone there to make sure he saw the right ring. Because, once again, one of my great ideas had gone wrong. I didn’t want James Redlands killing the wrong guy.

“Tools?” Torey was looking at his feet. “Tools?’ He looked back up at me. It looked like he was having trouble getting the words out.

“What, Torey?”

“You knew Vandy would kill him. That was part of it, too.” He wasn’t asking me.

Torey was exactly right. There was nothing I could say. I wondered what he thought of me. I took a deep breath. A family hustled by our car. Their little girl was laughing. The mother told her to be quiet. Torey broke the pause.

“Thanks.”

“Don’t mention it, kid.”

Most of the sirens had been turned off. There was a big crowd milling around outside the church. Hushed voices were spreading rumors instead of panic. I could see Vandy coming towards me. He looked very pissed off. I had a feeling what he might ask me. But I wasn’t going to answer him. It was too late for him to stop it anyway.

It was a blue sky. It was a Sunday morning.

I looked up at the few clouds there were. My mind was blank. I remember that Torey hugged me – a real hug. Consummatum est. It was finished. I was very tired.

I needed to rest.