Memories are always subjective.

Shared remembrances are especially fraught with danger. Sitting down with an old buddy and babbling on about “that day so long ago when we…” is a recipe for a screaming argument, psychologically debilitating ego assassination, or a real-life, up-close, bloody knife fight. It all depends on how trivial the memory is being discussed. The less important the event, the higher the likelihood of gory mayhem. The number of frosty pitchers of margaritas involved also may be a significant factor.

That’s why I never talk to Val about anything in our common past. I’ve seen her carve up a holiday turkey or two and prefer to keep my own giblets in a functional location. But if she asks about something in my lonesome “long-ago” — shit, that’s easy. I can tell my version without fear of contradiction.

“So why did you want to be a priest?” Val asked. Both her hands were on the wheel. There was, so far as I knew, no cutlery in the car, and I could detect no traces of rock salt on her lips. I’d been in the seminary years before I’d met Val. It seemed a safe road to travel — at least as safe as anyone can be when Val’s driving.

“I look great in black,” I said.

“It shows your dandruff.” Val either ran over a small man or a large squirel at that point. I bumped my head on the passenger side window.

“I like dressing up in neat costumes,” I said.

“Don’t start that again. I won’t do the nun fantasy again, Marty.” We were drifting towards a shared – and unpleasant for Val – experience. “I don’t understand this costume thing you’ve got in your sick little mind.” Val looked like she might start rummaging in the glove compartment for a Swiss Army scalpel or something.

I quickly pushed things back to my side of the past. “Something wrong with costumes? I had a Superman outfit when I was a kid.”

“You told me about that. That wasn’t a costume. That was a ratty, old, red bath towel that you safety-pinned around your neck.”

“You’re missing the point.” Just as the words came out of my mouth, Val grazed a pedestrian as if to illustrate how literally she could interpret a conversation. I raised my voice over the fading shouted obscenities of her near-victim. “The red towel made me feel invincible. In my Superman costume I could fly.”

“You broke an arm and a leg ‘flying’ off your roof heading for Susie Harlow’s window.” Val had a good memory. I’d only told her this story once, and she even remembered the names involved. “You just wanted to fly over and peep in her window. Pervert.”

Val was right, of course. I had been using my powers for evil instead of good. “Vaaaal…” I used the little boy voice, kind of a whine, actually. “It was a pivotal day in my young life — my bones… my innocence… shattered.”

“Well, that’s profound.” Val’s eyes went back to the road – finally.

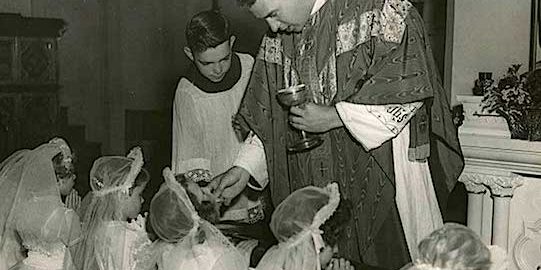

I babbled on, “It’s just that costumes have a certain power. Like when I was an altar boy. With the black cassock and the pure white surplice on, I felt close to God.”

“You mean you felt like you were better than everybody else.”

“Yeah.” I had to admit it. “There was that. Plus I was the one who rang the little bells that let everybody know that Jesus had arrived.”

“What an egomaniac.”

When she’s right – she’s right. I ignored her. “The coolest thing was being all dressed up and helping the priest give out communion. I’d hold this gold plate under everybody’s chin, and if there was a fumble, I’d catch the consecrated host.”

“Always with the sports metaphors.” Val cranked the wheel left and almost missed a pothole the size of Crater Lake.

I ignored her smart ass quip, bounced off the seat when the oil pan bottomed out, and let my stream of conciousness flow. “I liked communion. I got to look at everybody’s tongue. All the tongues in the parish. Mr. Jasper’s bumpy tongue. Mrs. Burnham’s paper thin tongue. Tammy Pepper’s purple tongue. Rusty Culp’s two-toned tongue. Eighty-five-year-old Mr. Cardiff’s tongue looked new, like a baby’s. Fourteen-year-old Frances Thedinger’s was crevassed like an ancient glacier. I used to dream about tongues.”

“You are sick,” she said.

“I’m a product of my upbringing,” I replied, in my defense.

“Yeah, your upbringing. How old were you when mommy dearest shipped you off to the seminary?”

“Thirteen.”

“Fucking crazy.” Val took her eyes completely of the road and lit up a cigarette.

I closed my eyes. Believe me, I didn’t want to watch if she wasn’t. “I was a mature thirteen.” God, I was even defending my mother.

“At thirteen a kid needs mothering, not a bus ticket to Monk-Land.” Val blew a thick cloud of smoke in my face. “A mom should be making her kid hot cocoa.”

I rolled down the window for some air. “My mom made me hot cocoa.”

“With schnapps.”

“Yeah, peppermint schnapps.” I was getting all nostalgic just thinking about it.

“So you went to the seminary when you were thirteen. Did you take your red towel cape?”

“No.” I was lying. I still keep the threadbare thing hidden in the bottom of my trunk. Val didn’t need to know.

“So what was the place like?”

“Assumption Semminary?”

“Yeah. It was north of here, right?”

“About fifty miles north in a little town called Optimism.”

“Ironic.”

“Antebellum.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean Optimism was like a little piece of the pre-Civil War south right here in the midwest. Way back when slave owners moved west and wanted to bring their ‘property’ with them, some of the old gentlemen built big houses up on the river’s edge bluffs. That’s how the town started.”

“Can’t grow cotton here.”

“Precisely. Farmers took over. Up there on the bluffs, looking down on Main Street, the old families kept faith with another time.”

“Jesus Christ, you must have read too much Faulkner between sitcoms.” Val’s sarcasm setting was on “11,” but she was listening.

“Assumption was supposed to pump out crispy new priests.”

“Nice image.”

“The seminary started in high school and went right through college. All the students on one ivy covered campus.”

“Let me guess. No girls.”

“God forbid.”

“And so he did.”

“It was an old campus; brick buildings, huge cottonwoods, backwards ideas. You know. But the education was good. I studied classic Greek, Latin, Plato, Socrates, Aquinas, all the K-Tel greatest hits of Western Civilization. I read Melville, Swift, Milton, Shelley, Jefferson…”

“All the dead white guys,” Val interupted. “Thought you told me that you got beat up a lot.”

“Yeah, it was great education punctuated with an occassional ass whupping.”

“Is this story going somewhere?”

“Of couse it is. Just listen, Val.” I was getting the feeling that this remeniscence, started so unintentionally, was getting me somewhere I needed to go. That’s the way the subconscious works. You start out talking about drowning kittens and end up finding your car keys.

“Well, cut to the chase.” Val was getting impatient – not unusual.

“The last time I had the shit kicked out of me was the end of term my junior year. Everyone was packing to go home the next day. The weird thing is, I wanted to stay. For all the school’s drawbacks, it was better than living with my mom. My Dad had left her by then.”

“Lucky guy, your dad.” Val snickered.

As the old saying goes, it was all coming back to me. For a guy who spent most of his time trying to supress the past, it wasn’t pleasant, but I was convinced it was important.

“I had just left the washroom in the old dormitory when I heard a kid crying in the stairwell. I followed the whimpering sound all the way up to the fourth floor landing. Nobody ever went up there. This was the high school underclassmen’s dorm. It had been built in 1905 — terrible old place with tiny windows. It was always full of this rusty colored dust from the old bricks, and poorly lit.”

“Appropriately spooky.”

“Yeah, it was spooky. Always smelled like old candlewax, too.”

“So you heard the kid crying, and you ran up the stairs to save him. Did you put on your superman towel first?”

“Very funny. I did run up to see what was up, and that’s when I saw him all curled up in the fetal position, sobbing.”

“The kid?”

“The kid – Doug Hunter.”

“Doug Hunter? Father Doug…” Val interupted again, but I interupted back. I didn’t want to lose my momentum.

“Yeah – Doug Hunter. I knew him a little, so I recognized him. He was a puny little guy. Anyway, when I got to him, I touched him. He was hot — like he’d just run a mile. He couldn’t catch his breath. He grabbed my hand and held on like a baby having a nightmare. I saw that his belt was undone.”

“Shit, his belt was undone? Shit!” Val looked pissed. “So you knew right then… no, wait. You were just an innocent kid yourself. You didn’t know what was going on, did you?”

“I knew, Val. I wasn’t that young anymore.” A memory came to the front of my head. No, not a repressed memory, not a recovered memory — I don’t have those. I almost let that damned memory loose. “I knew, Val. I knew. I knew, because when I was twelve…” I shut my mouth. I didn’t want that truth out there — not then.

Don’t know why I ever mentioned what happened to me when we started this story. But you see, at that moment in the car, talking to Val about the day so long ago at the seminary, I had one of those “flashbacks.” I remembered what had happened to me when I was twelve in every detail. Every second became real again. All the smells and the choking and the pain became real. Damn. Buy me another drink. I already told you and your tape-recorder about it way back when I started this spiel. I didn’t go into detail then. I won’t go into detail now.

Just know that I remembered it all – riding in Val’s car, talking too much. See, I started telling Val the story about what happened to Doug Hunter, and in the midddle of the telling, my own story started to butt-in. I had to slam all the watertight doors in my head to keep the past in its proper compartments. Well that’s trauma for you. It has a nasty way of popping up whenever the truth is loose.

I picked up the conversation as if I’d never started to explain myself to Val. I was hoping she’d let my little slip go by. She lit another cigarette as I went on with the story.

“Doug was there at my feet, and in the darkness, off to my left, I saw a man.”

“What happened to you when you were twelve?” Val was looking straight at me. Her Neon was going 45 mph in heavy traffic, and she didn’t look away from me.

“Let me finish, Val.”

“Sure.” She turned back to her driving and switched lanes just miliseconds before she rear-ended a rusty flatbed piled high with crushed Ford carcasses. “Go ahead. You saw a man?”

I took a deep breath, half because of the near-death experience and half from the vividness of the flashback I was still having. “It was dark, but I saw him. I didn’t know who it was. A dark figure was turning away from me and Doug’s prone pathetic body. It was a dark silhouette in a dark hallway…black on black…”

“Now you’re Richard Kimble?” Her sarcasm was back. I ignored it. When Val gets sarcastic, it means she’s listening.

“I attacked him.”

“Just like that? You attacked him?”

“I think it was the first time I ever really understood the word ‘fury.’ You know what I mean?”

“Biblical stuff,” said Val.

“Yeah, biblical. The guy was trying to get away down the hall that led to the other stairwell when I hit him in the back of his knees with all my strength. He didn’t buckle. He wasn’t tall but he was strong. His legs were solid. He straight-armed me and started down the stairs, almost running.”

“Jesus.”

I might have been punching the dashboard at that point — totally sucked into the past, I was back at the seminary. “I picked myself up. I flew after him and jumped up to grab him around his neck. I smelled ginger.”

“You smelled ginger?”

“Yeah. I was hanging onto him and I smelled ginger. I’ll never forget it.”

“So you choked him?”

“I tried. He stumbled two or three steps down to the landing on the third floor. It was like trying to strangle an oak tree. I just held on. It was all I could do. Somebody grabbed me from behind and pulled me off him. I was spun around and came face-to-face with Gerry Reese.”

“Gerry Reese?”

“A mean upperclassman jock-type who picked on me from time to time — he was close to graduation by then. He finished up at Assumption College – played football. Think ol’ Gerrry is a bishop somewhere in Indiana now.”

“And…”

“And Gerry hit me.”

“He hit you?”

“Must have knocked me out cold. I think he hit me more than once. But I wasn’t around consciously, so who knows — other than his excellency, Bishop Reese.”

“So Reese beat the shit out of you? You never lose fights. You usually run away.” Val was right.

“ Didn’t have a chance to run that time. Looking back, I think after the knockout I dreamt about whole wheat toast. Isn’t that strange?”

“Whole wheat toast?” She looked at me like it was the oddest thing I’d ever said to her. “Yeah. Strange.” Val took a deep drag. “So what happened to Doug Hunter?”

“When I woke up, Doug was wiping my face with a wet washcloth. ‘You’re going to be O.K. Don’t worry. It’s all over now. This shouldn’t have happened to you. It’s all my fault.’ He said shit like that — all in a monotone. ‘You shouldn’t have done it,’ he said. He helped me stagger into the tiny third floor chapel. I felt a little safer there – some instinctive sense of sanctuary. People were rarely beaten in the chapel. It was just eight rows of pews and a small altar. Above, on the wall, was a fresco of Mary, standing on a cloud, surrounded by cherubim. She was being assumed body and soul into heaven — The Assumption. I had hidden in there before.”

“When you got beat up.”

“Exactly. Oh, and back behind the altar was this little sacristy with a big old rod set way high on the wall in this little dressing nook. There was a whole bunch of old cassocks, surplices, and some fancy old vestments hanging there.”

“We’re back to that.” Val had that disgusted look on her face again. I stopped, thinking I’d lost her attention, because of that shared dress-up debacle. “Go on.” No, Val was still with me. “Go on.”

“Anyway, me and Doug were just sitting there on one of the pews, staring up at Mary. ‘You shouldn’t have done it. Haven’t you been in enough trouble?’ He was warning me, almost pleading with me not to say it, but I did. ‘I know what happened.’ That’s what I said, because it was true. I knew. ‘I know what happened,’ I said – or something like that. But he had to deny it. He had no choice. ‘Nothing happened. You don’t know what happened. You can’t say anything,’ he said. It was all shit like that. We were both scared. Maybe I was more frightened than he was. I knew he’d been…” I stopped talking. The word is hard for me to say.

“Abused.”

“Stupid word.”

“Abused?”

“Yeah, you abuse privleges. You abuse a friendship. You abuse chemicals. Abuse is a stupid word. The nuns used to call beating off ‘self-abuse.’ What the fuck is that?”

“So use the right word, Marty.”

“You know what I mean.”

“Say it, Marty.”

“O.K., he was raped. Raped. ‘Rape’ is the word.” I said it again, like I thought repeating the syllable would take the sting out of it. “He was raped.”

“Who do you pray to when something like that happens?” Val asked. She understood. She knew.

“Raped.”

“You O.K., Marty?”

“No.”

“What happened next?” Val probably figured it was best to just keep me talkng.

I took a shallow breath. It was the best I could do. “I had to ask him, ‘Who was it, Doug? Who did it?’ Gerry Reese hadn’t done it. He was just a dumb-fuck. Doug was really scared. I’d ask, and he’d just sit there. I’d ask again, ‘Who was it?’ He’d flinch. No answer. I asked again and again, ‘Who was it?’

“Who was it?” Val was right there in that moment with me.

“Doug just said, ‘No one. Forget it happened. Thank you for trying, but you’ll only make things worse. If I say anything he’ll…’ Of course that’s all he’d say. Was I supposed to beat it out of him? I just put my hand on his shoulder. We sat there for about an hour like that. Then he put his hand over mine and patted it three times, stood up, and left the room. I remember wanting to go home.”

“Jeeze, you wanted to go home to your mother? That was bad.” Val had slowed the car to about twenty. People were honking. She paid them no attention.

“We were friends of a sort after that. Doug and I would meet up in that chapel every once in a while and talk. We chatted about studies – bullshit like that. We never mentioned the time we first met. Near the end of my junior year, I went up to the old chapel for the last time. I was supposed to meet Doug. I was late. I had been arranging vestments in the main church. That was one of my favorite jobs at the seminary.”

“Costumes again,” Val said. This time there was no accusation in her words.

“Anyway, like I said, I was late. I hurried up the stairs and into the chapel. Only the Virgin was there, surrounded by naked babies — but no Doug. I heard a scraping noise. I didn’t know what it was or where it was coming from. I followed the sound into the sacristy. Doug was hanging from the rod. He had knotted three surplices together and made a noose. He was dying. His feet were kind of twitching, making the scaping sound. Then his feet were still. I was sure he was dead.”

“Jesus.”

“Jesus wasn’t there.” I realized I hadn’t been breathing myself. I took a deep breath and continued. “I grabbed at him. I was just tall enough to lift him with one arm, holding him against my body and pushing with my legs. I ripped the rod out of the wall. We ended up on the floor. Doug wasn’t breathing. I shouted for help, and I did CPR. I shouted and shouted and shouted.”

“Jesus,” Val said again. “You saved Doug Hunter’s life.”

“Sure. Saved his fucking life.”

“You regret it.”

I had to think about that for a second. “Maybe… I don’t know. I really don’t.”

“And you didn’t become a priest.”

“Yeah, decided to quit the clerical career track that very day. He lived and became a priest. Does that count as a save?”

“What happened to Doug isn’t your fault.”

“That’s not what the Chinese say. They think if you save a guy’s life you’re responsible for him from then on.”

“Fuck the Chinese.”

“That’ll keep you busy.”

“I like Asian men.” Val laughed. So, what did dear old mom say when you told her that you were cancelling her womb’s gift to the church?”

“She tossed back a big pitcher of martinis.”

“A real guilt barrage in the Hutchence household?”

“Precisely.”

“Well, fuck your mother.” It was a disturbing sentence, but I knew what Val meant.

“I was allowed back for my senior year as a non-vocational student.”

“What’s that mean, non-vocational?”

“Means I wasn’t studying for the priesthood. I was just a regular student then. I saw Doug just a few times after that. He recovered physically. The last time I saw him, we muttered a few social niceties. Then I remember him grabbing my arm. ‘Thank you for trying,’ he said. I hadn’t seen him since — until that night when he stood in the rectory door at St. Philomena, and you and I watched from the shadows.”

“Did you get raped when you were twelve?” Val’s question snapped me back into the present. I turned and looked at her. There was a long silence. “Well, did you get raped?”

I didn’t answer her.

After another silence, punctuated by the honking truck behind us, Val stopped the car. She turned and looked at me, and maybe she was even crying a little. “You would have made a great priest, Marty.” Then she kissed me.

“We’ve got to find Torey, Val.”

“I know, Marty. I know.”

“We have to find him. Help me find him.”

“I’ll help you, Marty. We’ll find Torey.

I think I might have cried a little bit then. I remember looking out the window as we drove north to Torey’s house. I remember how every little boy on a bicycle, or in a driveway, or playing in a yard – every kid we passed — looked like Torey at first.

I knew what happened to Doug that day in the dormitory. In the back of my mind, maybe I was starting to guess even then where all of this got connected to Terri and everything else that happened. But that’s all hindsight, isn’t it? Memories are subjective, after all.

I do remember that little boy, Doug Hunter, and the man who smelled like ginger. And I do remember the day I gave up on that school and all the costumes.

I

remember leaving Optimism behind me.